By Ashlie Bienvenu

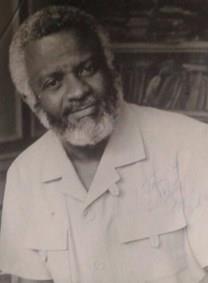

With the holidays right around the corner I’m sure everyone has had the opportunity to hear the carolers in the streets, or holiday music on the radio. So, for this issue, we will be looking back to a famous musical figure, Portia White. White, an Afro-Canadian from Nova Scotia, was admired for her ability to sing “spirituals with pungent expression and beauty of utterance (Historica Canada).” She was also described as having a voice which was “a gift from heaven (Historica Canada).” White is significant to the Black Community due to her efforts to break through the colour barrier and become the first Black Canadian to gain international fame as a concert singer (Canadian Encyclopedia). This can be seen through her early years and performances, her time as a teacher, and the awards and recognition that she later received.

Born in Turo, Nova Scotia, in 1911, to William A. White and Izie Dora White, Portia White was a descendent of Black Loyalists who fled to Nova Scotia, after the American Revolution, to escape slavery in the United States. Due to the fact that her father, William White, was a minister, Portia White began her music career at the age of six, singing in the church choir, under the direction of her mother, Izie Dora (Canadian Encyclopedia). By the age of eight Portia had learned parts from the Lucia di Lammermoor opera and was asked to sing on the Canadian radio (Black Past). White was so dedicated to her craft that she would walk 10 miles for music lessons (Canadian Encyclopedia). White participated in a Halifax music festival in 1935, 1937 and 1938, where she won the Helen Kennedy Silver Cup. White, a recognized talent, was given a scholarship by the Halifax Ladies’ Musical Club, to study at the Halifax Conservatory of Music, in 1939, with Ernesto Vinci. Once she completed her studies, in 1941, she began performing as a contralto, at the age of thirty (Canadian Encyclopedia). It was in 1944 that White made her first debut into United States, when she auditioned for the Metropolitan Opera, in New York City, which was managed by Edward Johnson. White was the first Canadian to sign with the Metropolitan Opera (Black Past). While White did not make any recordings in the studio, there are a few concert recordings, most notably the song Think on Me, which can be found (Canadian Encyclopedia).

In 1939, at the University of Dalhousie, White gained her teaching degree and began teaching in Africville. She later resigned her position, in 1941, to concentrate on her music career. Once she had retired from music, in 1952, due to physical difficulties and voice strain, White went back to teaching. She went on to teach voice at Branksome Hall, in Toronto. Some of her noteworthy students included “Dinah Christie, Anne Marie Moss, Lorne Greene, Don Francks and Robert Goulet (Canadian Encyclopedia).” Although White decided to go back to performing part-time, in the mid-1950’s, her performances were sporadic through the fifties and sixties. One notable performance for White, however, was a performance for Prince Philip and Queen Elizabeth II, in Charlottetown, in 1964 (Canadian Encyclopedia).

White’s legacy lives on in the fact that “her popularity helped to open previously closed doors for talented blacks who followed (Black Past).” A Maritime newspaper, the Halifax Chronicle-Herald, once dubbed her the “singer who broke the colour barrier in Canadian classical music (Historica Canada).” Due to her lifelong achievements, and contribution to the Black community, “White was named a ‘person of national historic significance’ by the Government of Canada (Canadian Encyclopedia),” in 1995. White was also awarded with a stamp of herself in 1999, a sculpture in front of a Baptistst Church in her hometown in 2004, and an award in her name, the Portia White Prize, which is given every year to “an outstanding Nova Scotian in the arts (Canadian Encyclopedia).” White was also awarded the Dr. Helen Creighton Lifetime Achievement Award posthumously in 2007 (Canadian Encyclopedia).

Bibliography

King, B. N., So, J. K., and McPherson, J. B. (June 21, 2007). Portia White. Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/portia-white-emc/.

Portia White. Historica Canada. Retrieved from http://blackhistorycanada.ca/arts.php?themeid=22&id=2.

White, Portia (1911-1968). Black Past. Retrieved from http://www.blackpast.org/gah/white-portia-1911-1968.

For Full Version of Semaji November 2017 Click Here