Canada’s Black Walk Of Fame

By Ashlie Bienvenu

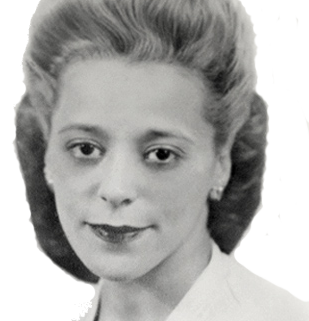

As there has been a lot of recognition of this historical figure in the past few years, with her inclusion in the Canadian Heritage Minutes and the decision to place her on the new ten dollar bill, I thought it would be appropriate to start our new series, Canadian Black Walk of Fame, with Viola Desmond. This series not only looks at the life and contributions of these important figures in Canada’s Black history, but also looks at the way that they have shaped Canadian society with their contributions and actions. With Ms. Desmond, we will look at her background of fighting for an equal opportunity, for herself and her community, her courageous actions when her basic human rights were violated, her impassioned battle with the courts to fight for her rights, and the rights of her community, and her lasting impact on Canada as a Civil Rights pioneer.

Viola Desmond’s dream, of owning a Black beauty salon, was not easily attained in the 1940’s. Not only was it difficult for Black people to open a business, but very few beauty schools would admit Black students. In fact, Desmond had to travel all the way to Montreal get accepted into beauty school (Annett). She then went on to open her own salon that provided services for Black women; however, she didn’t stop there. Desmond expanded her business over the years, and also created a beauty school that Black women could study in, so they would not have the difficulty of finding a school like she did (CBC News). Desmond’s sister said that this was due to her passion for people; “she inspired them and she inspires us (CBC News).”

Even though Desmond did a lot to help her community before 1946, it wasn’t until November 1946, that Desmond managed to “raise awareness about the reality of Canadian segregation (Black History Canada).” The incident that sparked this awareness began when Desmond had traveled to New Glasgow, looking to expand her business, when she encountered car trouble. Looking to for something to do while waiting for her car to be fixed, Desmond decided on watching a movie, not knowing that this theatre segregated its clients. When Ms. Desmond asked the ticket booth for a seat in the first few rows, due to her nearsightedness, the ticket-seller refused to sell her a ticket for the main floor; she could only get the balcony, even though she was capable of buying the more expensive floor tickets. Angry that she would be denied access to a seat, simply because of the colour of her skin, Desmond walked into the main floor and sat in a chair. This then resulted in the manager telling her to leave because she did not pay for a floor seat, to which Desmond responded she would be willing to pay for the extra cost. The manager refused to sell her a floor seat ticket, due to the fact that she was Black, and called the police, who brutally dragged her out of the theatre, injuring her hip and knee (Heritage Minutes). Desmond was then put into a police cell for the entire night, where she “maintained her composure, sitting bolt upright in her cell all night long, awaiting her trial the following morning (Heritage Minutes).”

Desmond was then charged with tax evasion and given a fine of twenty-six dollars, due to the fact that main floor seats were one penny more than balcony seats. Ironically, even though her “real ‘offence’ was to violate the Roseland Theatre’s implicit segregated seating rule (Heritage Minutes),” race was never mentioned. After paying the fine, Desmond tried twice, unsuccessfully to get the decision appealed at the Nova Scotia Supreme Court (Heritage Minutes). In fact, Desmond went to her grave, in 1965, “without any acknowledgment of racial discrimination in her case (Annett).” This “miscarriage of justice (Heritage Minutes)” was only acknowledged in 2010, in a posthumous pardon presented by Nova Scotia’s Lieutenant-Governor Mayann Francis (Heritage Minutes).

This, then, brings us to Desmond’s memory in current times and her impact on Canadian society. Ms. Desmond is often called the Rosa Parks of Canada, even though Desmond’s standoff occurred nine years before Parks. This is conveniently glossed over in Canadian history, due to the Country’s pattern of “whitewashing history (CBC News).” Be that as it may, Desmond was key in setting a precedent of fighting for civil rights in Canada. Even though the appeals of the trial were not won, “her story and her vigilant activism through the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People were important factors in the eventual abolition of the province’s segregation laws in 1954 (CBC News).” Desmond’s legacy of civil rights advocacy has not gone unnoticed recently. In 2018, she will be the first Canadian female, as well as Black figure, to be featured on the Canadian ten dollar bill. She is also the first Black female to get a Canadian Heritage Minute (Annett).

Therefore, Desmond was one of the first key figures to fight for the Black community’s civil rights. She may not have been successful with her appeals of the trial; however, she managed to bring to light the implicit pattern of racism in Canada. According to Finance Minister Bill Morneau, “Viola Desmond’s own story reminds all of us that big change can start with moment of dignity and bravery (Annett).”

Bibliography

Annett, E. (2016, Dec. 09). Who’s the woman on Canada’s new $10 bill? A Viola Desmond primer. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/women-on-banknotes-viola-desmond/article33264617/

Black History Canada. Viola Desmond. Historica Canada. Retrieved from http://www.blackhistorycanada.ca/profiles.php?themeid=20&id=13

CBC News. (2016, Dec. 08). How civil rights icon Viola Desmond helped change course of Canadian history. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/viola-desmond-bio-1.3886923

Heritage Minutes. (2016). The story of Viola Desmond, an entrepreneur who challenged segregation in Nova Scotia in the 1940s. Historica Canada. Retrieved from https://www.historicacanada.ca/content/heritage-minutes/viola-desmond

Picture: https://heritageday.novascotia.ca/content/2015-honouree

For full version of Semaji March 2017 Click Here